William Henry Hudson may have faded from prominence, but on the centenary of his death, Professor Clive Webb from the University of Sussex reveals Hudson’s life and work still offer value and relevance to the Sussex landscape today

Seven thousand miles from where he was born, William Henry Hudson lies in his final resting place at Worthing’s Broadwater cemetery. On his death, The Times eulogised that he was ‘unsurpassed as an English writer on nature’. His many admirers included the likes of Virginia Woolf and Joseph Conrad, who exclaimed of Hudson that he wrote ‘like grass that the good God made to grow’.

Yet Hudson only attained his reputation after long years of penury and obscurity and is today largely forgotten. This year is the one hundredth anniversary of his death, an opportune moment to remind ourselves of his contribution to literature and his important connections to Sussex.

The son of an American couple who had settled as sheep ranchers in Argentina, Hudson was born on 4th August 1841 in Quilmes, near Buenos Aires. His formal education was limited. Instead he read his way through the books in the family farmhouse and wandered alone across the pampas where he cultivated his love and knowledge of the natural world, a life described in his autobiography Far Away and Long Ago (1918).

Hudson endured many early hardships. He contracted rheumatic fever as a teenager, which left him with a weakened heart. His mother died soon after, followed a few years later by his father.

Unfastened from the mooring of his family, Hudson trained with the Argentinian military before travelling to Patagonia. His interest in natural history also led to him collecting bird skins for the Smithsonian Institution in Washington DC. In April 1874 he took the fateful decision to sail to England.

Settling in London, Hudson suffered years of poverty. For a time, he slept in Hyde Park before moving into a boarding house. In 1876 he married his landlady, Emily Wingrave. They were an unconventional couple. A former soprano, Wingrave stood only as tall as her husband’s elbow. Only after her death did Hudson learn she was more than a decade his senior. Although loyal to one another, theirs was a companionable rather than romantic relationship that bore no children.

The Hudsons struggled financially. Emily became bankrupt but inherited another boarding house and taught music lessons to make ends meet. William took up his pen, producing numerous books on natural history including The Naturalist in La Plata (1892) and Idle Days in Patagonia (1893). He also wrote novels, among them The Crystal Age (1887) and Green Mansions (1904). None, however, met with critical or commercial success until they were republished late in Hudson’s life.

It was only in these later years that Hudson found recognition. He was a founding member of the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds in 1889, eventually serving as its chairperson. Friends also lobbied for him to receive a civil service pension in 1901, the year after he finally became a British citizen.

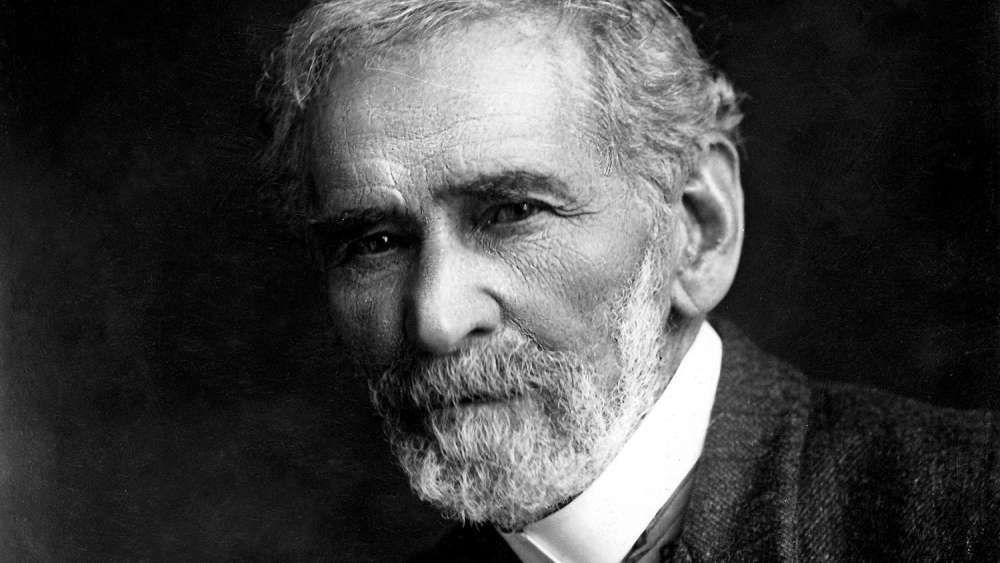

Portraits show how he bore some of his earlier adversity. He stood over six feet tall, his back and shoulders stooped, the eyes in his bearded face melancholy. In the words of his friend and biographer Morley Roberts, ‘He looked like a half-tamed hawk which at any moment might take to the skies and return no more.’

Hudson wrote not only about South America but also about the flora and fauna of his adopted homeland. Dressed in starched collar and tweed coat with field glasses in hand he roamed across the countryside, recording his encounters with wildlife in such work as Hampshire Days (1903) and A Shepherd’s Life (1910). Of particular interest to readers of this magazine are his impressions of Sussex in the 1900 book Nature in Downland.

The naturalist knew Sussex well. He holidayed in Shoreham and wandered on foot across the entire county, his travels during the long, dry summer of 1899 the basis of his book. Hudson was enchanted by many of the villages in which he wandered around churches and cemeteries, admired old timber framed houses and drank the ale of local inns. Alfriston, Ditchling and South Harting were among the rural communities that won his affection.

He was less enthusiastic about larger towns. The seafront at Brighton afforded him some pleasure despite the overpowering smell of fried fish. But he loathed Chichester. The city smelled so bad, he claimed, that it induced a sickness he described as a bad case of ‘the chichesters’. Even by the standards of a county whose inhabitants he believed were too familiar with the bottle, Hudson was appalled by locals’ ‘perpetual swilling’.

What redeemed Chichester was its cathedral. For the modern rambler it is still possible to share with Hudson the panoramic view of the spire framed by the rolling South Downs, to see as he did how ‘it pulls the scene together, and gives it a unity and distinction which it would never have possessed if by chance men had not built that spire precisely where it stands’. Other cathedrals might be architecturally finer, he wrote, but none harmonised closer with the surrounding landscape.

Hudson wrote poetically but precisely about the plants and animals that populated the Downs. To read him is to see the colours and smell the scents of flowers from Viper’s bugloss to Wild scabious. It is also to learn in intimate detail of all sorts of animal life, especially birds.

He afforded the same forensic attention to the farming communities who lived and laboured on the Downs. At a time when many people never left the places where they were born Hudson believed it possible to note the distinctive human characteristics of different counties. Sussex folk were ‘good-looking people, and good to live with’, he observed, though not so much as the population of Somerset. Hudson also admired their ‘stability of character, their sturdy independence of spirit, and, with it, patient contentment with a life of unremitting toil’.

But the people of Sussex had their vices as well as their virtues. ‘In some of the villages,’ Hudson claimed, ‘illegitimate children are as plentiful as blackberries’. More plentiful still was the amount of alcohol they consumed, far more than in any other county. Thankfully they possessed ‘remarkably steady heads and carry their liquor well’.

As much as he delighted in the abundance and diversity of Sussex wildlife, Hudson also despaired of its increasingly rapid decline. Hudson accepted the passing of the black oxen that pulled farmers’ ploughs across county fields.

But he was less sanguine about the decimation of birds that fell victim to the Victorian obsession with hunting, egg collecting and feather wearing. ‘It may be said, without injustice,’ he wrote, ‘that Sussex has distinguished itself above all counties...in the large number of native species it has succeeded in extirpating during the present century.’

The bird song that once filled the Sussex landscape had, Hudson observed, been sadly muted by the loss of so many species. Bustard, chough, and hen harrier were among the birds that had disappeared from the land and the sky.

For Hudson one of the most potent symbols of that loss was the stone curlew. Chancing upon a solitary bird as he strolled across the South Downs the naturalist lamented, ‘perhaps that wild yet human-like whistle is uttered in my hearing was its last farewell’.

A decade or so after the publication of Nature in Downland, Hudson’s wife, by then in declining health, moved from London to Worthing. Hudson remained in the capital but loyalty to Emily made him a regular visitor to the south coast until illness also left him bedridden. He died on 18th August 1922 and was buried alongside Emily, who passed away the previous year.

One hundred years after his death the Sussex scenery through which Hudson walked would be familiar to him in some respects but unrecognisable in others. Our coast and countryside are still places of outstanding natural beauty. Yet climate change, urban development and intensive agriculture have had a profoundly negative impact. Birds beloved to Hudson such as the swift and wheatear are now endangered.

In this centennial year we can best honour the legacy of this pioneering naturalist by supporting conservationists in protecting and promoting Sussex wildlife. Hudson’s writing is an important message from the past about the need to protect and promote the future of the natural world.

It’s a Dog’s Life: Let it Snow... Somewhere Else

It’s a Dog’s Life: Let it Snow... Somewhere Else

It's a Dog's Life: Foods are Seasonal, Treats are Perennial

It's a Dog's Life: Foods are Seasonal, Treats are Perennial

It's a Dog's Life: World Animal Day

It's a Dog's Life: World Animal Day

It's A Dog's Life: Never Assume...

It's A Dog's Life: Never Assume...

Fostering Happiness at Raystede

Fostering Happiness at Raystede

It's a Dog's Life: Why So Much Sport?

It's a Dog's Life: Why So Much Sport?

It's a Dog's Life: A Partly Political Broadcast

It's a Dog's Life: A Partly Political Broadcast

It's a Dog's Life: Our Hobbies are Not the Same

It's a Dog's Life: Our Hobbies are Not the Same

It's a Dog's Life: Our Currency is Biscuits

It's a Dog's Life: Our Currency is Biscuits

It's a Dog's Life: Teddy & the Dragon

It's a Dog's Life: Teddy & the Dragon

Paws for a Cause

Paws for a Cause

Kids Zone: Lambing in Spring

Kids Zone: Lambing in Spring

It's a Dog's Life: Access Denied

It's a Dog's Life: Access Denied

It's a Dog's Life: February is not just for Pancakes

It's a Dog's Life: February is not just for Pancakes

It's a Dog's Life: Cleaning Up

It's a Dog's Life: Cleaning Up

Top 10 Garden Birds to spot in Sussex

Top 10 Garden Birds to spot in Sussex

Top Tips: Keep Your Pets Safe this Bonfire Night

Top Tips: Keep Your Pets Safe this Bonfire Night

Advertising Feature: Plan Bee

Advertising Feature: Plan Bee

It’s a Dog’s Life - The Quiet Life

It’s a Dog’s Life - The Quiet Life

What should you be looking out for in your Sussex Garden this Summer?

What should you be looking out for in your Sussex Garden this Summer?