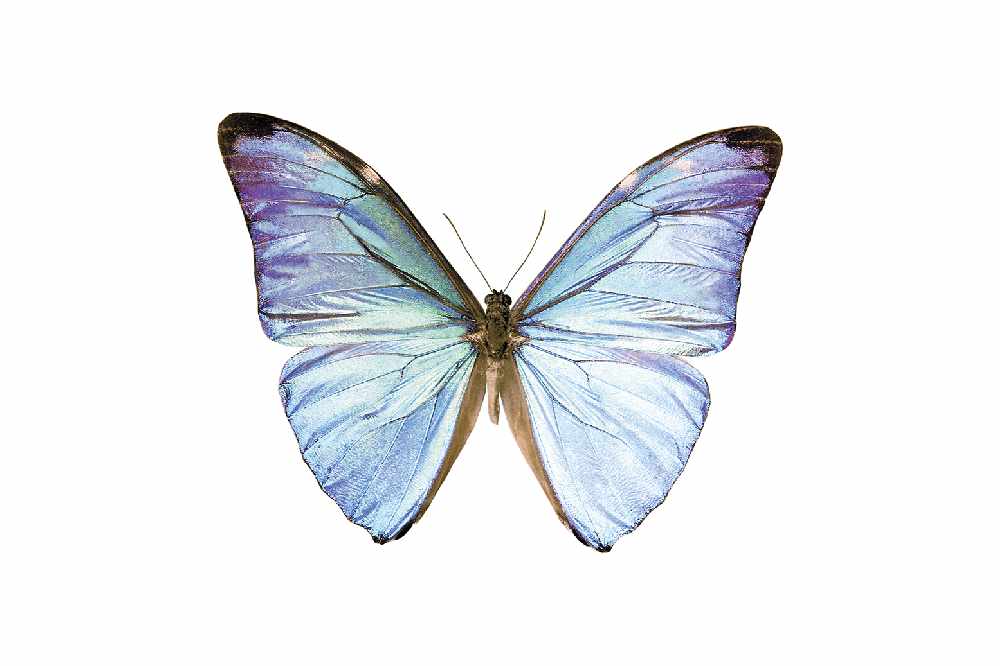

Missing the flutter of summer butterflies, Ruth Lawrence discovers how these delicate creatures winter out the cold months, and looks forward to their return in the spring

While the New Year may herald fresh beginnings for us, nature is at her slowest; branches are bare, fields are empty and the woods are quiet and still.

One of the sights I miss in winter is the glimpse of a passing butterfly. So symbolic of warm summer days, they seem to disappear once the cold weather bites. Yet all lay waiting in one of four forms throughout the darker, shorter days. Britain has nearly five dozen types of butterfly and just over half spend the winter as caterpillars, the remainder existing as either eggs or chrysalises while only six hibernate as adults.

Their life cycles are perfectly timed so that the caterpillars emerge alongside their specific food plants; some depend upon a single plant and here on the South Downs, we have a perfect example of nature’s synchronicity. Caterpillars of the Chalkhill blue and Adonis blue both feed on one plant alone, horseshoe vetch, found on the unimproved chalk grassland of the Downs. If both caterpillars emerged simultaneously, they would be in competition, so the Adonis caterpillar emerges at the winter’s end and the Chalkhill six weeks later, by which time the Adonis has become a chrysalis, leaving the vetch for the hungry Chalkhill.

The only adult butterflies to survive in a state of torpor over winter are the colourful species such as the Red Admiral, Brimstone, Comma, Peacock and Small Tortoiseshell. They lie dormant in sheds, log piles and tree hollows, waiting to be ignited by warmth. Sometimes, an uncharacteristic prolonged winter sunny spell can awaken them, which can be fatal if there is no food to sustain them. If you find a dormant butterfly over winter, leave it undisturbed so long as it is dry and sheltered; if it has woken in your house because of the central heating, some action can be taken to help it return to dormancy.

It can be placed in a shoe box with ventilation holes and after being kept in a cool dark place for an hour, it can be placed somewhere sheltered and dry like a woodshed to sleep out the winter. If you decide to let it remain in the box in a dry cold place, make sure you cut a couple of slits 5cm high by 1cm wide in the box so it can emerge in spring when it awakens. The coldness makes sure it does not wake before its food becomes available and the dryness avoids fatal fungal infections.

Special insect hibernation boxes are available or can be built; they resemble bird boxes with the same waterproof roofs, but have slits instead of a hole in one side and can be placed with the slits facing the brightest part of the garden.

For me, knowing that the butterflies are waiting out winter in one form or another makes the short days more bearable with the promise of delicate wings taking to the skies once more.

It's a Dog's Life: A Day for Teddys Everywhere

It's a Dog's Life: A Day for Teddys Everywhere

It’s a Dog’s Life: Let it Snow... Somewhere Else

It’s a Dog’s Life: Let it Snow... Somewhere Else

It's a Dog's Life: Foods are Seasonal, Treats are Perennial

It's a Dog's Life: Foods are Seasonal, Treats are Perennial

It's a Dog's Life: World Animal Day

It's a Dog's Life: World Animal Day

It's A Dog's Life: Never Assume...

It's A Dog's Life: Never Assume...

Fostering Happiness at Raystede

Fostering Happiness at Raystede

It's a Dog's Life: Why So Much Sport?

It's a Dog's Life: Why So Much Sport?

It's a Dog's Life: A Partly Political Broadcast

It's a Dog's Life: A Partly Political Broadcast

It's a Dog's Life: Our Hobbies are Not the Same

It's a Dog's Life: Our Hobbies are Not the Same

It's a Dog's Life: Our Currency is Biscuits

It's a Dog's Life: Our Currency is Biscuits

It's a Dog's Life: Teddy & the Dragon

It's a Dog's Life: Teddy & the Dragon

Paws for a Cause

Paws for a Cause

Kids Zone: Lambing in Spring

Kids Zone: Lambing in Spring

It's a Dog's Life: Access Denied

It's a Dog's Life: Access Denied

It's a Dog's Life: February is not just for Pancakes

It's a Dog's Life: February is not just for Pancakes

It's a Dog's Life: Cleaning Up

It's a Dog's Life: Cleaning Up

Top 10 Garden Birds to spot in Sussex

Top 10 Garden Birds to spot in Sussex

Top Tips: Keep Your Pets Safe this Bonfire Night

Top Tips: Keep Your Pets Safe this Bonfire Night

Advertising Feature: Plan Bee

Advertising Feature: Plan Bee

It’s a Dog’s Life - The Quiet Life

It’s a Dog’s Life - The Quiet Life