The Booth Museum in Brighton is home to an original presentation of the natural world as one Victorian saw it. Generations later, it’s also a timely reminder that extinction is all around today as Michael Blencowe explains

Images by Jade They

There is a wonderful museum that lurks unassumingly on Brighton’s Dyke Road, the tree-lined avenue connecting the city to the rolling chalk hills of the South Downs. The Booth Museum of Natural History was built in 1874 by ornithologist Edward Booth. Booth loved birds and he enthusiastically pursued his passion with his double-barrelled shotgun. Inside the museum a display cabinet holds Booth’s gun along with the battered waterproof sandals and sou’wester he would pull on before tramping Britain’s marshes and moors hunting his quarry.

Born in 1840, three years after Queen Victoria took to the throne, Booth’s behaviour, which today seems archaic, was typical of a nineteenth century naturalist. Victorian society was enthralled by the natural world and they demonstrated their admiration through coveting, collecting and categorising it. Birds, butterflies, ferns, eggs, seaweeds, shells, you name it – if the Victorians could get their hands on it they would kill it, skin it, stuff it, press it and pin it. Their collections and curios, local or exotic, were displayed as a statement of their wealth, status and intellect.

Just beyond the Booth museum’s entrance there’s a reconstruction of a typical dimly lit parlour, the showcase of some Victorian homes. Amid the shadows, the iridescent wings of tropical birds glimmer within glass domes and metallic blue butterflies lie meticulously ordered in serried ranks in the drawers of polished mahogany cabinets.

Collecting turned into an obsession for certain men with time, money and means; country clergy, recently retired colonels from the front lines of Empire, or, in the case of Edward Booth, those who had inherited a substantial family fortune. When Booth’s expanding bird collection threatened to engulf the family home he built this museum to house his overflowing hobby.

Yet while other Victorian museums crammed their cabinets with regimented rows of birds in strict scientific order Booth was a pioneer in presenting his specimens posed within three-dimensional replicas of their natural habitats called dioramas. In one, a yellowhammer broadcasts a silent song from a facsimile of a farmyard fence. In another, two swooping skylarks defend their nest from a predatory stoat.

Inside each diorama a different species is immortalised in a frozen moment, a recreation of the life that Booth had taken away. Upon his own death in 1890 Booth bequeathed his museum to the people of Brighton.

Over time the Booth museum has slowly absorbed and amassed an incredible wealth of almost one million natural history specimens; everything from microscope slides of bacteria to mounted mammals, anthrax to zebras. Today the museum remains a special place for everyone, from dinosaur obsessed children to scientific researchers, to people like me who value the inspiration, information and escape this wonderful museum provides.

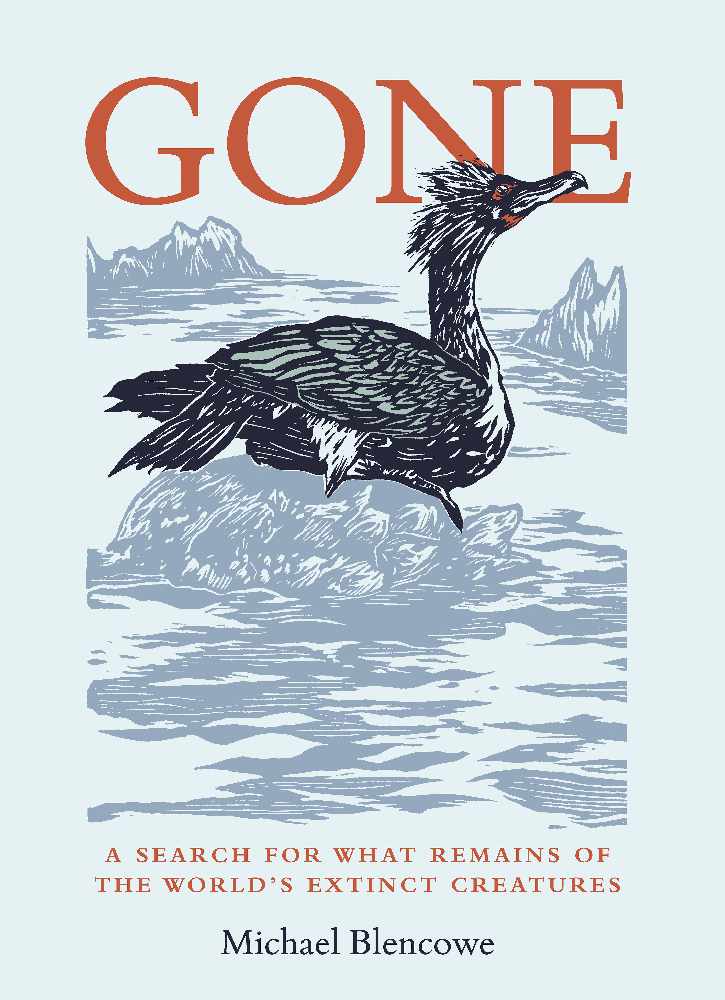

A few years ago, a curated display of extinct animals reconnected me to my dinosaur obsessed childhood. I was captivated by some mysterious animals, which had tantalisingly disappeared from our planet relatively recently: the enigmatic Dodo, the elegant Great Auk, the delicate Xerces Blue butterfly and the gigantic Steller’s Sea Cow. I was inspired to take a journey, a pilgrimage in search of the places where these animals once existed, and I sought out what remains of them today in the world’s natural history museums.

My travels in search of their legacies took me to the fern-filled forests of New Zealand, the streets of San Francisco and the museum storerooms of London, Copenhagen, Paris and Helsinki. But extinction is not restricted to rainforests and remote islands. It is happening all around us, right now. Species are slowly vanishing from our local areas to be lost in turn from our districts, our counties and our countries.

One Sussex species has vanished from the world completely. The Ivell’s sea anemone was only ever known to exist in one place; Widewater Lagoon on Lancing seafront. Its disappearance in 1997 has entitled this beautiful creature to membership of an exclusive club. One in which animals once found in Britain are now globally extinct, a dubious honour it shares with the woolly mammoth. Ironically, after searching for extinct animals around the globe I found myself floating on a lilo just 15 minutes from home, searching for a lost species. It’s a reminder that we live on an increasingly fragile planet.

Gone: A search for what remains of the world’s extinct creatures by Michael Blencowe and published by Leaping Hare Press is out now

December Book Reviews

December Book Reviews

If You Ask Me: Flo’s Virtual Bookshop

If You Ask Me: Flo’s Virtual Bookshop

Kids Zone: Christmas Traditions

Kids Zone: Christmas Traditions

Book Reviews: November Novels... and more!

Book Reviews: November Novels... and more!

What to Watch in October 2024

What to Watch in October 2024

Kids Zone: Spooky Spider's Webs

Kids Zone: Spooky Spider's Webs

If You Ask Me: Humanity's Greatest Invention

If You Ask Me: Humanity's Greatest Invention

If You Ask Me: A Desert Island Drag

If You Ask Me: A Desert Island Drag

Kids Zone: Mud Kitchens

Kids Zone: Mud Kitchens

What to Watch in July 2024

What to Watch in July 2024

Kids Zone: Ice Block Treasure Hunt!

Kids Zone: Ice Block Treasure Hunt!

What to Watch in June 2024

What to Watch in June 2024

A Gourmet Escape on the Eurostar: London to Amsterdam with Culinary Delights in Almere

A Gourmet Escape on the Eurostar: London to Amsterdam with Culinary Delights in Almere

If You Ask Me: Train Announcements Have Gone Off the Rails

If You Ask Me: Train Announcements Have Gone Off the Rails

If You Ask Me... Never Argue with an Idiot

If You Ask Me... Never Argue with an Idiot

Kids Zone: Mosaic Art

Kids Zone: Mosaic Art

What to Watch in April 2024

What to Watch in April 2024

If You Ask Me: The Jobsworth and the Frog

If You Ask Me: The Jobsworth and the Frog

What to Watch in March 2024

What to Watch in March 2024

If You Ask Me... Politicians need a Translator

If You Ask Me... Politicians need a Translator